Choosing a backend database: SQL vs Document vs Columnar

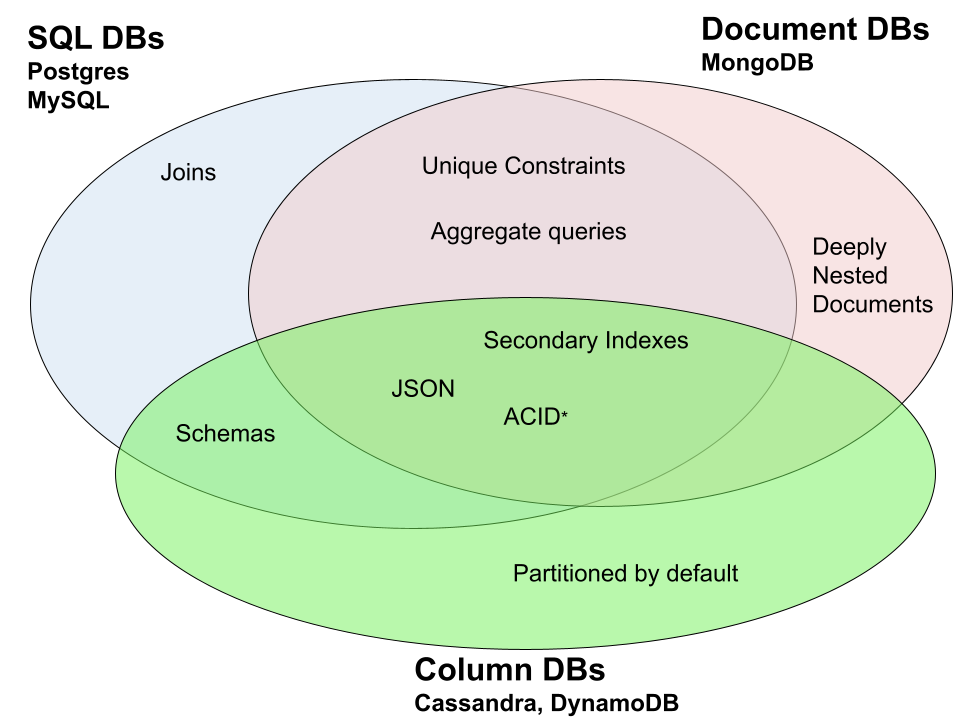

In the evolving landscape of databases, the lines distinguishing one type from another have blurred as features converge. How do you pick the right one for your needs? Here's a venn diagram showing which features are shared and which are unique.

* = Mongo added ACID support in version 4.0

Guidelines

Join Queries: Opt for SQL databases if relational data handling is crucial.

Deep Document Model: Choose a document database for intricate document structures and partial updates.

Schema Flexibility: While the allure of schemalessness might steer you towards NoSQL, keep in mind that modern SQL databases offer JSON column support.

Write-Heavy Workloads: If your primary operation is writing and you require scalability, a columnar DB might be your best bet.

Whether or not one uses a NoSQL database, many of the principles of NoSQL/document databases are helpful when designing an application. For example, ask yourself, how could I design a system where I wouldn’t need to use joins (see Data Denormalization)

Massively scaling up

One can vertically scale instances quite a lot these days, for example AWS supports up to 128 vCPU individual instances, but that is still only so much.

Clustering: SQL and document DBS support setting up replica sets where you have one writer instance and many reader instances. This allows distributing your read load across multiple instances (as long as your application can tolerate eventual consistency.) This setup can also provide high availability if the cluster has automatic failover setup.

Sharding/partitioning: Scaling a heavy write load is more complicated. Cassandra and other columnar DBs supports this out of the box since every instance is a writer. Document DBs can be configured to store data in different instances based on some hash function. For SQL, a common approach is using code which runs multiple copies of the DB and provides an interface in front to handle routing and joining data across shards (see Vitess for MySQL and Citus for Postgres)

Conclusion

Examine the features listed in the Venn Diagram and see if any are essential for your project. For many use cases, any database will work, but these databases do have details that become important for large projects. Once costs start to become a concern, I think engineers should become familiar with the database internals, since using each database in an ideal way based on how it was designed can lead to substantial efficiency improvements.

Other Considerations

MySQL vs PostgreSQL

Over time, these have become more similar e.g. both allow adding columns without locking, json columns, common table expressions and unicode. Note:

Compatibility: While there is a standard for SQL, no database adheres to it perfectly as a result applications over time often become dependant on the type of database. For example, Wordpress primarly only supports MySQL.

Data clustering: Both DBs stored data in groups called "pages" (typically 8 KB for Postgres and 16 KB for MySQL). MySQL stores row data together based on your primary key. Postgres stores row data together mostly based on insertion time. This will have different effects depending on your type of primary key.

| Primary Key Type | Performance Considerations |

|---|---|

| UUID | PostgreSQL ordering rows by insertion is likely to be more useful. |

| sequential id | Performance will be similar |

| compound key e.g. (user_id, group_id) | MySQL performance will likely be better, since related data is stored together. |

This means that if your primary key is a sequential id, the dbs effectively work the same. If your primary key is something else, like the compound key e.g. (user_id, timestamp), this can affect performance substantially.

Connection cost: With Postgres, each new connection spawns a new process which means there's a memory overhead of 5 to 10 MB per connection. Connections in MySQL don't use separate processes and so have much less overhead.

Licensing: MySQL has a more restrictive open source license. For SaaS usages though this doesn't matter. However, if you're creating an application that users will install locally and includes the db, then PostgreSQL's more permissive license may be important.

Row deletion: PostgreSQL does most updates by inserting a new row and for deletes it does not remove the data immediately, but rather just marks it as being no longer visible. To remain performant and save space, PostgreSQL needs to periodically cleanup the old rows, this process is called vacuuming.

Data denormalization principles

Document DBs really benefit from denormalization since they don't support joins, but these principles are equally relevant for optimizing SQL databases with read-heavy applications.

The overall idea of denormalization is including data a single table that would have otherwise been split into multiple related tables or storing multiple copies of the same data. Here's some principles and then how they would apply when designing a schema for a movie database.

Avoid enum tables: Instead of making a genre table, you could just store the genre_name as text (or an enum type) in the movie table.

Avoid many-to-many tables: Instead of making a movie_actors table with a movie_id and actor_id, you could have an actor_ids column with an array type like INT[] (this is postgres specific)

Precompute aggregates: Instead of running a count(*) query to get the number of oscar nominations an actor receieved, store an oscar_nomination_count in the actors table. This count would then need to be updated each time a new nomination is inserted.

These principles increase data locality and rely on the principle that typical applications do much more reads than writes. So these make reads simpler while also make writes more complicated and slower, but since they're rarer this is a net win.

By Thomas Hansen, published on 2023-10-15